NAEPC Webinars (See All):

Issue 45 – October, 2024

Into the Great Wide Open: Planning for Childfree Individuals

By: Jennifer B. Goode, J.D.

First comes love, then comes marriage, then comes…a childfree lifestyle for many individuals in today’s America. Earlier this year, the Center for Disease Control reported that the general fertility rate in the United States —the projected birth rate over a group’s lifetime—had fallen by 3% to a historic low.[i] Separate research suggests that this decreased fertility rate may partially reflect a conscious decision by many individuals to forgo having children. For example, a 2024 Pew Research Center survey found that 47% of nonparent participants ages 18 to 49 said they were either not too likely or not at all likely to have children someday, with 57% of such individuals noting that they simply did not want children.[ii] Additionally, a recent Michigan State University study found that one in five adults in Michigan were deliberately choosing to remain “childfree”.[iii] Since Michigan is demographically similar to the United States as a whole, this finding could mean that approximately 50 to 60 million Americans are also choosing a childfree lifestyle.[iv]

This trend will undoubtedly impact many sectors of American life, including estate planning. Consider the roles frequently played by a child or descendant under a client’s estate plan—beneficiary, fiduciary, and steward. How should estate and financial planning professionals prepare for this change to the planning landscape?

Understanding the Childfree Client

To answer this question, estate and financial planning professionals must first consider the childfree client’s needs and what sets them apart from others. This is a tricky task, as much of today’s research focuses broadly on nonparents without distinguishing between individuals who want but cannot have children, those who have yet to decide, and those who are committedly childfree.[v] As we await further research concentrating on the childfree population, planners may glean a few insights from existing studies as well as past surveys of nonparents in general.

Involvement of Chosen Family[vi]

Current studies suggest that there are few intrinsic differences between childfree individuals and other populations when it comes to life satisfaction and personality.[vii] Rather, this group’s distinguishing characteristics may lie in their relationships with others. While those without children may experience enhanced levels of connection with parents, siblings, nieces, nephews, and spouses,[viii] the “usual suspects” from the perspective of many planning professionals, their nonparent status may most significantly impact their relationships with extended family members, neighbors, and friends (their “chosen family”).[ix]

Multiple studies of nonparents both in the US and abroad suggest this cohort is especially likely to cultivate and rely on chosen families for various forms of support. For example, a 2016 study comparing the personal networks of both parents and nonparents in Germany found that nonparents had a greater propensity to incorporate their chosen family members into their personal networks.[x] In addition, these nonparents were able to rely on their chosen family members for informational and emotional support to a greater extent than the parents who were studied.[xi]Another analysis of nonparents across Europe found that they were more likely than parents to both give and receive financial and social support to and from their chosen family members, especially nonrelatives.[xii]

Indeed, nonrelative chosen family members may function as a nonparent’s preferred source of social support, even when biological family members are available. Consider a study of personal networks among aging gay men in New York, of whom only 15% reported having at least one child.[xiii] When compared with other aging New Yorkers, these men were significantly more likely to report having at least one close friend or confidant within their personal network and had, on average, three times as many friends within this network as other aging New Yorkers.[xiv]Importantly, these relationships were not made to the exclusion of traditional familial relationships. A majority of the survey participants reported that they were in contact with family members, with 16% of participants acting as caregivers for a family member.[xv] Yet despite the presence of family members in their networks, the survey participants rarely selected these individuals as a source of support if a partner or spouse was not available, relying instead on friends or simply themselves.[xvi]

The preference for chosen family structures may impact a childfree individual’s financial planning due to (i) the use of financial transfers to chosen family members as a means of solidifying these relationships; and (ii) an increased reliance on formal care in the individual’s later years.

Solidifying Relationships – The childfree client may seek to solidify social connections with chosen family members through financial transfers during the client’s lifetime. For instance, a 2009 study of lifetime transfers from over 20,000 Americans ages 51 and older and their spouses found that nonparents were much more likely to make gifts to friends and extended family members, with their increased likeliness to give as compared to parents bearing little relationship to resource level.[xvii] That is, even when resources would allow for gifts to both descendants and other individuals, parents were still less likely than nonparents to give to friends and extended family. Why? Researchers hypothesized that gifts to chosen family satisfied a similar social purpose as gifts to children and more remote descendants, meaning that those who could solidify relationships with children and descendants did not feel the same need to do so with other parts of their social network.[xviii] Where gifts served impulses beyond solidifying relationships with the recipients, such as a sense of obligation to one’s parents or altruism, the presence of children either did not, or less significantly, impacted the likelihood of such gifts.[xix]

Thus, a childfree client is not only inclined to create a more diverse personal network than an individual with children, but such client’s ability to make gifts to chosen family may bolster and deepen these relationships. Further, if we consider the importance of chosen family to the support of nonparents as they age, it becomes increasingly clear that positioning childfree clients to make gifts to these individuals is central to their long-term physical and mental well-being.[xx]

Formal Care – Reliance on chosen family members may not completely insulate the childfree client from the costs of aging without children and its related financial uncertainty. Research suggests that nonparent older individuals are more likely to turn to formal sources of support earlier and to a greater degree than parents[xxi] and that a majority of nonparents believe that those with children have it easier with respect to receiving care as they age.[xxii]

Compared to parents, nonparents’ tendency toward formal care may stem from several dynamics inherent in the parent-child relationship. Studies show that spouses and children provide a level of intense, unpaid care unmatched by the care provided by other relatives and friends.[xxiii] Additionally, a strong degree of age-related homophily among friend groups may bear some responsibility for this care discrepancy. For instance, a recent survey of adults within the San Francisco Bay area found that 81% of the participants ages 21 to 30, and 52% of participants ages 50 to 70, only maintained non-kin relationships with those within 5 years of their own age.[xxiv] In other words, outside of family members, the majority of individuals in both age groups surrounded themselves with those of approximately the same age. Extrapolating these results to the larger US population would leave over half of nonparents, who tend to lean more heavily on friends as a source of support, with similarly- aged networks and thus susceptible to the negative impacts of such network’s aging at a time when the nonparent typically requires the most assistance.

No matter the reason, a childfree individual’s greater reliance on formal care may meaningfully impact their spending and gift-giving habits. For instance, a recent study of nonparents aged 50 and older found that over a third of participants were very worried about having enough money as they age.[xxv] And it is not hard to see why! Consider the current cost of long-term care across the country illustrated in the chart below.[xxvi] An individual would need to save over $1.2 million to support 20 years of care in an assisted living facility.

| Monthly Median Costs (2023) | ||

| In-home Care | Community and Assisted Living | Nursing Home Facility |

| Home Maker Services—$5,720 | Adult Day Healthcare—$2,058 | Semi-Private Room – $8,669 |

| Home Health Aide—$6,292 | Assisted Living Facility—$5,350 | Private Room – $9,733 |

Further, an individual without an obvious candidate to serve as their attorney-in-fact or trustee may need to engage a professional fiduciary to aid in their financial and medical decision-making later in life. Such professionals’ fees add to a childfree client’s sense of financial pressure. For example, corporate trustees typically charge a percentage of the trust assets under management, often, 1% to 2%, while other professionals may charge an hourly rate.[xxvii] Compared to the paltry compensation, if any, received by a child serving in one of these roles, the involvement of a professional fiduciary can increase the liquid capital needed to support a childfree individual’s spending over their remaining lifetime in a manner that may impact their investment preferences and nonessential spending goals.

Creation of Charitable Legacy

Just as they establish unique connections with extended family members and non-relatives, childfree individuals may also maintain a special relationship with charitable organizations and causes. Notably, studies have found that nonparents who give to charity, either during life or at death, consistently give more assets than their counterparts with children. For example, in the study cited above comparing the lifetime transfers of parents and nonparents, researchers noted that nonparents who made charitable gifts gave roughly two to four times more than the parents studied, depending on marital status.[xxviii] Nonparents also are much more likely to include charities under their estate plans and transfer larger amounts to them at the nonparent’s death. For instance, an analysis of the 1995–2006 Health and Retirement Study found that decedents with a will or trust but without grandchildren were five times more likely to have included a charitable bequest than decedents with grandchildren.[xxix] Further, nonparents made up 9.75% of the decedents who incorporated a charitable bequest in their estate plans while accounting for 51.86% of the charitable dollars transferred by all decedents.[xxx]

Research regarding nonparents’ underlying preferences for charitable giving is limited, in part due to a lack of data distinguishing between those with and without children. Consider that most tax filings documenting charitable gifts do not inquire about a taxpayer’s parental status. However, the disproportionate share of testamentary and sizable charitable transfers made by nonparents suggests that there is significant overlap between these communities. Planning professionals may draw two conclusions from certain trends among larger donors who donate at death: namely, an increased interest in gift restrictions and a preference for perpetual charitable entities.

Gift Restrictions – First, the childfree client may respond more favorably to the imposition of gift restrictions on a testamentary gift. Prior research has documented both that: (i) the ability to impose restrictions on a charitable gift increases the likelihood of a donor’s giving, and (ii) larger charitable bequests more commonly feature gift restrictions.[xxxi] As nonparents are more likely than parents to make charitable bequests, and the size of their charitable gifts made both during their lifetimes and at their deaths dwarfs those of parents, documented gift restrictions may apply more frequently to nonparents’ charitable transfers.

Why do restrictions increase the likelihood of giving and giving in larger amounts? Donors may include such restrictions, in part, to amplify the emotional impact of the gift by allowing the donor to view the transfer as extending and preserving the donor’s legacy. At least one legal scholar and researcher in the area of testamentary charitable giving has previously sought to use psychology’s “terror management theory” to explain this phenomenon.[xxxii] This theory holds that reminders of one’s own mortality enhance positive feelings toward “in-groups,” social groups with which one identifies, while stoking negative feelings toward “out-groups.”[xxxiii] Thus, if a charitable gift serves to strengthen an individual’s sense of belonging among an in-group, this gift may generate feelings of symbolic immortality, or an impact that can “live on” after the donor’s death.

Further, childfree individuals may find gift restrictions especially useful in generating this emotional response. Researchers have previously posited that when selecting an in-group, those with children may default to their sense of identity as parents.[xxxiv] Thus, parents may focus on their children and more remote descendants in structuring their estate plans, which could partially explain the lower prevalence of testamentary charitable planning among this group. Nonparents, however, may identify with a broader array of groups in the absence of this default identity. As such, gift restrictions may serve both as a means of designating a specific in-group among this wider pool of potential communities and to define their legacy, especially when the donor cannot rely on younger generations to steer the gift’s posthumous implementation.

Perpetual Entities – Secondly, childfree individuals who create charitable structures may have a greater preference for perpetual entities. For example, a 2004 survey of German philanthropic foundation founders noted that nearly half were nonparents who cited an absence of heirs as a catalyst for establishing a foundation.[xxxv] Moreover, such nonparent founders were more likely to describe their foundation as “giving to posterity.”[xxxvi]

Indeed, the administrative characteristics of a nonparent’s charitable structure, as well as the timing of its inception, correspond with an increased likelihood of a perpetual existence. A survey of private foundations showed that entities with paid staff and whose founder was no longer living were most likely to plan for perpetuity.[xxxvii] This is because the foundation’s purpose was not focused on the founder’s involvement or enjoyment nor to act as a tool for family engagement.[xxxviii] As nonparents tend to favor charitable bequests at death and may look to formal sources of administrative support due to an absence of descendants, it suggests that any resulting charitable structure is likely to seek perpetuity for ongoing impact.

Impacts on the Planning Process

Given the aforementioned findings, how might planning professionals effectively implement these findings and modify the estate planning process to best serve childfree clients?

Identifying the Parties at Play

As a first step, professionals working with nonparents, including childfree clients, should consider that these individuals may have a more varied circle of loved ones compared to clients with children or other descendants. Therefore, it is important to revisit the methods used to collect information about the client and their planning goals. Consider the typical client questionnaire used by estate planning counsel to solicit information and background facts. Does this questionnaire ask about individuals beyond the traditional family structure? While a client may not think to mention the friends or neighbors central to their daily life without prompting, an estate plan that ignores such individuals could prove disruptive to the client’s social network. To better capture these relationships during the intake process, counsel may consider asking open-ended questions, such as “Who do you turn to for help in your daily life?” or “Who belongs to your social support network?”[xxxix]Counsel may also consider inquiring about existing financial transfers while steering clear of restrictive phrases that imply some form of financial dependency. For example, “Do you regularly receive funds from or give funds to any individual?” rather than, “Do you provide financial support for anyone in your life?”

Blended Fiduciary Roles

Conversations with childfree clients regarding potential fiduciaries should include the possibility of spreading a fiduciary’s responsibilities among multiple people or organizations, including professional fiduciaries, where appropriate. As noted above, a childfree individual may weave together a diverse patchwork of support, with members displaying varying levels of tolerance for intensive tasks.[xl] Thus, such client may find it possible to identify a friend or neighbor willing to play a smaller, administrative role but who cannot or will not perform daily tasks. The introduction of shared duties or directed fiduciary roles, including those held in tandem with a professional fiduciary, may allow these individuals to assume responsibilities for which they feel best suited without the fear of being overwhelmed or unsupported. If counsel remains focused solely on family members to fill these roles, whether due to a failure to identify other individuals within the client’s personal network or from an insistence that a sole individual meet all the position’s demands, the client may, to their detriment, default to naming someone who is not a preferred care provider or who is otherwise removed from the client’s daily needs. For example, a client may appoint a niece or nephew who lives far away and accordingly cannot keep track of the client’s day-to-day support requirements, as opposed to a friend or neighbor who may have a deeper understanding of the client’s lifestyle and habits and who could respond to the client’s needs in a timelier fashion.

Additionally, a childfree client’s estate planning documents may require fine-tuning to support fiduciary flexibility. Consider the drafting of a durable financial power of attorney for a childfree client. Many statutory forms prohibit an agent acting under a power of attorney from delegating responsibilities to a third party unless the client affirmatively grants such authority.[xli] However, an individual who can comfortably commit to less frequent or intensive tasks but may require assistance to provide for the client’s daily needs may view the authority to delegate as a precursor to accepting a fiduciary role. Since a childfree client is more likely to turn to piecemeal care solutions, this default drafting position may warrant revisions. Further, counsel may want to include additional language indemnifying an agent who exercises the authority to delegate while setting clear parameters for the selection and monitoring of a delegee.[xlii] Provisions pertaining to the appointment of successor agents may also require special consideration. If the client lacks intergenerational ties, as a childfree client might, due to the previously noted age-related homophily among friends, the client may struggle to appoint a long line of successors over time and face aging out of the financial power of attorney’s effectiveness. To avoid such outcome, counsel may consider granting a then-serving agent or other individual the ability to appoint a successor agent in the future, perhaps from a class of individuals or with other guidelines.[xliii] Counsel may also wish to provide for the appointment of a professional fiduciary within this line of succession and set guidelines for allowable compensation.

Focus on Smaller, Repeated Gifts

When engaging in transfer tax planning, childfree individuals may especially benefit from smaller transfers implemented over a longer time horizon, rather than large one-time transfers to an irrevocable trust. As noted above, a childfree client’s concern for later-in-life costs and support may heighten their desire to maintain control over and access to substantial portions of their wealth. Additionally, the childfree client may have a more diverse social network that evolves over time as their bonds with extended family, friends, and neighbors fluctuate. For this reason, small, repetitive transfers, such as a gift of the annual exclusion amount,[xliv]or transfers that allow the client to retain the fair market value of the transferred asset but gift future appreciation, such as a sale to an intentionally defective grantor trust (“IDGT”) or a grantor retained annuity trust under which the retained annuity’s present value matches the fair market value of the initial trust contribution (a “zeroed-out GRAT”), may be considered. These strategies can alleviate worries about outliving financial resources and enable redirection of assets to a new beneficiary in the event of a change in relationships.

Preserving Flexibility for Larger Transfers

What if a childfree client wishes to utilize the current historically large federal gift and estate tax exemption or plan prior to the sale of a business or other liquidity event? In those situations, a long-term transfer strategy may not deliver the same benefit as a one-time, large gift to an irrevocable trust. Assuming a childfree client feels comfortable with losing access to the trust funds, they may still want to preserve flexibility with respect to the trust’s beneficiaries. How can counsel achieve this goal?

Limited Power of Appointment – First, counsel may consider granting one or more individuals a lifetime or testamentary power under the trust agreement to appoint the trust assets to individuals beyond the original prescribed beneficiaries.[xlv] This “limited power of appointment” should not trigger inclusion of the trust assets in the client’s taxable estate or that of the powerholder provided that (i) the power is not held by the client and (ii) the powerholder cannot appoint property to the powerholder, the powerholder’s estate, or creditors of the powerholder or the powerholder’s estate.[xlvi] To avoid a potential taxable gift by the powerholder at its exercise, counsel may also wish to grant any such lifetime power either to a non-beneficiary of the trust or a beneficiary entitled only to distributions for health, education, maintenance, and support.[xlvii] Additionally, counsel should limit the exercise of such power in exchange for services provided to the trust or the client to prevent potential inclusion of the distribution in the recipient’s gross income.[xlviii]

Even more importantly, counsel should take care to advise the client that such power of appointment is personal to the powerholder. This means that the exercise of such power, unlike a distribution by a trustee, need not further the client’s intent in creating the trust. Additionally, the trust’s beneficiaries may have no recourse if they feel the power is exercised inappropriately. To address this lack of accountability, counsel could consider including special instructions regarding the power’s exercise. For example, the trust agreement could limit the appointee pool to include only those individuals with whom the client has had personal contact during the calendar year immediately preceding the distribution.[xlix] Counsel could also consider granting an independent trustee[l] or other third party the authority to remove, add, or otherwise change the power of appointment.

Trust Protector – If the client would rather expand the beneficiary pool directly, thereby granting additional individuals the rights of a trust beneficiary, including the right to reasonable information and the ability to bring suit for a trustee’s breach of trust, counsel could consider authorizing a “trust protector” to do so. Again, to avoid potential estate tax inclusion issues, the client should not function in such role, nor should any trust beneficiary in order to avoid making a potential taxable gift.[li]

Yet, there remains a wrinkle to this potential solution. Namely, counsel will need to determine whether the trust protector can act as a non-fiduciary, since a fiduciary cannot add additional trust beneficiaries, thereby diluting the interests of the original beneficiaries, without inviting a potential fiduciary breach.[lii] This task is not as easy as it first appears. Consider that some state statutes require that a trust protector serve as a fiduciary, while others simply apply a presumption subject to alteration under the trust agreement.[liii] Other state laws expressly allow a trust protector to serve as a non-fiduciary.[liv]

If counsel creates an irrevocable trust in a state that allows a trust protector to function as a non-fiduciary, is that the end of the analysis? Maybe not. Statutory trust law cannot fully waive certain basic fiduciary requirements, underpinning the very essence of trust law. The Restatement (Third) of Trusts defines a trust as a “fiduciary relationship with respect to property, arising from a manifestation of [the settlor’s] intention to create the relationship”.[lv] As such, while the trust agreement can alter certain aspects of a trustee’s duties and obligations, a trust’s terms cannot entirely erode the fiduciary nature of the trustee-beneficiary relationship. As the Restatement (Third) of Trusts notes:

Although a trustee’s duties, like trustee powers, may be affected by the terms of the trust, the fiduciary duties of trusteeship are subject to minimum standards that require the trustee to act in good faith and in a manner consistent with the purposes of the trust and the interests of the beneficiaries.[lvi]

Therefore, if we accept that some base level of fiduciary relationship must exist between the trustee and the trust’s identified beneficiaries, can a trust protector, or any other individual, take an action that could significantly impair the trustee-beneficiary relationship? Indeed, some legal scholars have argued that trust protectors must be subject to the same floor of duties required for trustees.[lvii]

Counsel should also note that the grant of such power to change beneficial interests may trigger certain income tax consequences. More specifically, it may qualify as a power to add to the beneficiaries designated to receive the trust’s income or principal under IRC Section 674, prompting “grantor trust” status. IRC Section 674 deems the settlor of an irrevocable trust as the owner of the trust’s assets for income tax purposes if the trust allows the settlor or a nonadverse party to exercise control over the disposition of the trust assets.[lviii] That is, unless the only person who can exercise discretion over the distribution of the trust assets is an individual with an interest in not making a distribution, for example, a trust beneficiary who could otherwise enjoy those assets, the settlor will be treated as the owner of the trust assets and all income, and capital gains generated by the trust will flow through to the settlor’s personal income tax return. Typically, a settlor can avoid this treatment when desired by relying on one of several exceptions to such treatment under IRC Section 674.[lix] However, these exceptions will not apply if any individual has the lifetime power to add beneficiaries to the trust.[lx] Since a beneficiary adverse to the exercise of such power of appointment would likely risk making a taxable gift by its exercise, this makes it difficult to expand the trust’s beneficiary pool without triggering either negative gift tax consequences for the powerholder or grantor trust status for the settlor.

Noncharitable Purpose Trust – What if the client likes the limited power of appointment’s absence of fiduciary risk but wants to tie its use, in an enforceable manner, to their intent in creating the trust? Is there a trust structure that could support a middle path between the two options discussed above? Under common law, an individual could not create an enforceable trust benefiting an indefinite class of beneficiaries, that is, a class that cannot be identified at the trust’s outset, because neither the trustee nor a court asked to intervene, could definitively determine all the parties that might qualify as beneficiaries and to whom the trustee owed a fiduciary duty.[lxi] Thus, the direction to a trustee to distribute property for the benefit of one’s “friends” would assign the trustee a power, but not a fiduciary duty, to distribute trust property to such individuals as the trustee selects, with any trust property not distributed by the trustee reverting to the property’s original owner or the owner’s heirs at law.[lxii] Put simply, this type of direction equated to a power of appointment under common law. However, all of that changed with the introduction of the noncharitable purpose trust.

While noncharitable purpose trusts were first recognized in connection with the care of animals and cemetery plots, their use has been expanded by the adoption of such structure under the Uniform Trust Code (“UTC”). UTC Section 409 provides that:

Except as otherwise provided in Section 408 [pertaining to trusts created for the care of an animal] or by another statute, the following rules apply:

- A trust may be created for a noncharitable purpose without a definite or definitely ascertainable beneficiary or for a noncharitable but otherwise valid purpose to be selected by the trustee. The trust may not be enforceable for more than [21] years.

- A trust authorized by this section may be enforced by a person appointed in the terms of the trust or, if no person is so appointed, by a person appointed by the court.

- Property of a trust authorized by this section may be applied only to its intended use, except to the extent the court determines that the value of the trust property exceeds the amount required for the intended use. Except as otherwise provided in the terms of the trust, property not required for the intended use must be distributed to the settlor, if then living, otherwise to the settlor’s successors in interest.

Thus, if a childfree client lives in a state that allows for a noncharitable purpose trust under statutory language like the above, counsel may create an irrevocable trust to further a general purpose without identifiable beneficiaries to whom a trustee would owe a fiduciary duty. Further, if this statute allows for a longer trust period, the trust could continue throughout the client’s lifetime or beyond.[lxiii]

What type of purpose might a childfree client’s noncharitable purpose trust adopt and what are the potential tax ramifications of funding and administering such a trust over time? As noted above, a childfree individual may wish to utilize trust funds to strengthen and support ties among their chosen family subject to changes in this group’s membership. Counsel then could provide that the trust’s purpose is to support the well-being of those within the client’s social network and provide certain metrics by which the trustee can determine who qualifies as a part of this network, such as communication or interaction with the client. Indeed, such trust furthers a legitimate public policy of ensuring support for an individual who might otherwise struggle to secure care in their later years.[lxiv]

But would the client’s social behaviors function as a power over the distribution and use of the trust funds in a manner that could undermine their transfer tax goals? For example, federal gift tax law provides that a transfer to an irrevocable trust is considered “incomplete” for gift tax purposes if the transferor retains a power to name new beneficiaries or to shift beneficial interests among the beneficiaries.[lxv] Similarly, a decedent’s taxable estate includes property previously transferred by the decedent for less than adequate and full consideration and over which the decedent retained either: (i) the right to designate the person who will ultimately possess or enjoy the property or its income, or (ii) a power to alter, amend, revoke, or terminate such transfer.[lxvi] Would the client’s ability to create new social relationships, and thus introduce new potential recipients of trust property for the trustee’s consideration, qualify as a power to add beneficiaries that could make a gift to trust incomplete for gift tax purposes, or draw the trust assets back into the client’s taxable estate at the client’s death?

While there is no clear precedent on point, counsel could likely rely on the trustee’s singular role in trust distributions to argue against such negative transfer tax consequences. For example, Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”) Section 2511 provides that it is a donor’s power over transferred property that keeps a gift from being complete.[lxvii] Additionally, IRC Sections 2036 and 2038 similarly require that a decedent hold a right or power through which the decedent can control the trust property’s possession or enjoyment.[lxviii] Here, the client has no authority or power over the trust property. It is the trustee, not the transferor, that exercises sole authority over how, when, and to whom the trust makes distributions.[lxix] Indeed, settlors of irrevocable trusts frequently interact with trust beneficiaries in ways that may enhance the beneficiary’s likelihood of receiving trust funds without negative transfer tax consequences. Consider the parent who creates an irrevocable trust for the benefit of their children and then counsels a child to engage in activities such as starting a business, buying a home, or pursuing higher education for which the trust can make distributions. This type of behavior is not typically problematic from a transfer tax perspective due to the settlor’s inability to enforce such distributions from the trusts for these purposes. Query whether this behavior differs materially from that of the childfree client proposed above in any manner other than the involvement of children.

To avoid other avenues for estate inclusion, counsel will need to draft and fund the trust with an eye toward avoiding a reversion to the settlor. First, it is crucial to draft the trust’s purpose broad enough to utilize all the trust’s assets. If the trust’s value ever exceeds the amount required to achieve its stated purpose, a court may require a distribution of trust assets back to the settlor or the settlor’s heirs.[lxx] Here, the support of the settlor’s social network will likely avoid a funding ceiling since the funds could support various paid activities, gifts, and other benefits for these beneficiaries. The settlor should select contingent beneficiaries to receive the trust assets in the event of its termination. If the trust supports the client’s social network during their lifetime, the trust will terminate at the client’s death and the trust should provide for a distribution among the then-potential recipients to avoid inclusion of the trust assets in the client’s taxable estate.[lxxi]

Counsel should note that the trustee’s ability to make distributions to an amorphous beneficiary group may qualify as a power to add to a class of individuals who may receive the trust’s income or principal under IRC Section 674, as there is no set beneficiary group at the trust’s outset. This means that the client is unlikely to have a choice as to the income tax treatment of the proposed noncharitable purpose trust and must contend with grantor trust status.

Navigating Shared Interests

If a childfree client pursues a more traditional trust strategy, another consideration for counsel is the administrative complexities presented by tying together a diverse beneficiary pool under a single trust structure. Compared to planning for descendants who are necessarily connected to one another by birth or adoption, and for which one may assume similar goals such as furthering broader family values, the interests of a childfree client’s chosen family may diverge or even conflict. Consider the differing income needs and investment time horizons of an older client’s similarly aged friends versus those of younger neighbors or nieces and nephews. How can counsel prevent, or at least protect a childfree client’s fiduciaries from, potential discord leading to everything from administrative hassle to fiduciary litigation?

Modifying Notice Requirements – As a starting point, counsel may arm the trustee with additional control over the flow of information to the trust’s beneficiaries. State laws vary regarding a beneficiary’s right to details about the trust and the trustee’s duty to respond to beneficiary requests for information, including the extent to which an irrevocable trust’s settlor may waive such requirements.[lxxii] Indeed, as of 2024, 15 states allow an irrevocable trust’s settlor to fully waive all notice requirements under the trust agreement.[lxxiii] Such waivers or limitations may avoid both: (i) the interference of contingent remaindermen whose interests may never vest due to the needs of current beneficiaries, and (ii) the administrative burden of contacting numerous beneficiaries who share no other connecting tie and thus are unlikely to share a central representative such as a parent or similarly positioned beneficiary.

Of course, one downside of limiting beneficiary notice and involvement is a lack of access to certain administrative fixes and limitations for liability available only through beneficiary consent. For example, most states allow for a limited statute of limitations period following a trustee’s disclosure of all trustee actions taken during the reporting period, sometimes referred to as an “accounting.”[lxxiv] To allow a trustee to utilize limited notice requirements while still availing themselves of accountings and other administrative tools such as nonjudicial settlement agreements, counsel may provide under the trust agreement for the appointment of a designated representative or surrogate to receive information on behalf of the beneficiaries, if state law provides for such role.[lxxv] This individual can then represent and bind beneficiaries for purposes of accountings, settlement agreements, and so on. Further, counsel should consider how best to protect such designated representative or surrogate from liability. If the individual is treated as a fiduciary subject to the same duties as the trustee, this would effectively shift the exact same level of liability from the trustee to the designated representative or surrogate. Hardly a definitive solution! Where possible, counsel may consider clarifying that an appointed designated representative or surrogate must act in good faith but is not subject to more intensive fiduciary constraints and incorporate related indemnification provisions for actions taken in such a role.

Clarifying Investing Focus – As noted above, asset management is another area of complexity for the trustee of a trust serving diverse beneficial interests. Unlike a trust structure intended to further an older generation today with remaining property passing to a younger generation of the same family in the future, current and remainder beneficiaries of such trust may not share demographic characteristics or personal values, or even know one another. In this context, a trustee may struggle to defend investment actions under the duty of impartiality that requires the trustee to give due regard and fair consideration to all beneficial interests.[lxxvi] Counsel may aid the trustee in this task by documenting the client’s wishes as to any beneficial interests that may take precedence over others, whether in the trust agreement or through a nonbinding letter of intent. Additionally, counsel may leverage a unitrust structure that requires the distribution of a set percentage of the trust’s value each year in place of an income interest. This allows the trustee to invest the trust assets to achieve a greater total return, rather than investing to generate income to the detriment of remainder beneficiaries or investing for growth to the detriment of income beneficiaries. For example, if a trust benefits both older friends and younger family members, utilizing the unitrust structure may satisfy both parties’ needs. Such a structure pursues greater total return that enhances the annual unitrust payments designed to meet the current spending needs of the older beneficiaries without hindering the growth of the trust’s principal available to the younger beneficiaries over the trust’s term. Lastly, counsel might consider including annual distribution ceilings for certain beneficiaries, as these ceilings set realistic expectations regarding the potential outflow of assets to each beneficiary and potentially dissuade beneficiaries from pushing for additional investment upside to the detriment of other beneficial interests.

Separating Conflicting Interests – Counsel should also ensure that a trustee managing a trust with potentially divergent beneficiary interests can divide the trust if circumstances warrant. This division can occur through a power to divide or decant under either the trust agreement or statutory law. For example, UTC Section 417 permits the division of a trust into two (2) or more separate trusts with prior notice to all qualified beneficiaries, provided that the division does not impair the rights of any beneficiaries or adversely affect the trust’s material purpose. Alternatively, state decanting statutes permit trust distributions in further trust for the benefit of one (1) or more current beneficiaries and could allow for the allocation of the original trust’s beneficiaries among two (2) or more new trusts, as needed.[lxxvii] In addition to authorizing the division or decanting of trust assets, counsel should protect against unintended income tax consequences by permitting the trustee to distribute trust assets on a non–pro rata basis.[lxxviii] Further, counsel may look to avoid negative transfer tax issues by allowing the trust’s division or decanting without the consent or action of the client or the trust’s beneficiaries, if permitted under the trust agreement or state law.[lxxix] And, for any trust exempt from generation-skipping transfer tax, the trust agreement should prohibit: (i) any decanting that will extend the time for vesting beyond any life in being at the original trust’s creation plus 21 years or, alternatively, beyond 90 years, and (ii) any other modification that will extend vesting beyond the trust’s original rule against perpetuities period.[lxxx]

Case Study

To better understand how the above findings and suggestions can impact the estate planning process for a childfree client, consider the planning needs of Layla, age 65. Layla is a childfree woman living in Austin, Texas, who currently owns $15 million of liquid assets, real estate worth $3.5 million, and tangible personal property worth $1 million. While Layla would like to engage in transfer tax planning to avoid a federal estate tax liability at her death, she worries that she may need her remaining assets to support her lifestyle if she requires formal care in the future, including moving into an assisted living facility. At this point, she is also unsure about who should benefit from the bulk of her wealth at her death, or during her lifetime. She maintains good relationships with her nieces and nephews, but her siblings are wealthy, and Layla is not convinced that her nieces and nephews truly need additional assets. While she is charitably inclined, she also wants to make an impact on those individuals who play a regular role in her day-to-day life. But what if those individuals change over time? How can she plan for her future when she is not sure who will be part of it?

As a first step in the estate planning process, her counsel engages Layla in a conversation about her loved ones and personal network. Layla relays that she frequently interacts with her siblings, nieces, and nephews, along with neighbors and a few friends from college and her previous employer. While she feels close to her siblings and their children emotionally, she does not see them frequently because they live far away. In contrast, she spends most weekends with her friends and neighbors and their families. In fact, members of one family that lives geographically close to Layla refer to her as “Granny Layla” due to her years of sharing holidays and helping them with childcare. Layla has previously contributed to 529 Plan accounts for the family’s children, and Layla likes to make small gifts to her friends and neighbors when she sees a need or for a special event.

When discussing her potential fiduciaries, Layla’s counsel asks who Layla would turn to for help if she needed someone to physically assist her at home or help her with financial matters. Layla responds that she would likely ask one of her friends or neighbors for help, especially because her family members live miles away. However, Layla notes that she does not wish to burden these friends and neighbors with all the responsibilities of serving as an agent under a power of attorney or as trustee of a trust. To ensure that Layla receives care from those who know her best but without unnecessarily taxing her chosen family relationships, Layla’s counsel suggests two paths. First, Layla could consider appointing one of her local loved ones to serve in these roles, provided they have authority to delegate any part of the role they do not feel comfortable undertaking. Alternatively, Layla could appoint a local loved one alongside one of her siblings and divide their duties based on her relationship with each person and their specific skillsets. Layla decides to discuss these options with those most likely to serve in these roles to determine which option best meets everyone’s needs and capabilities.

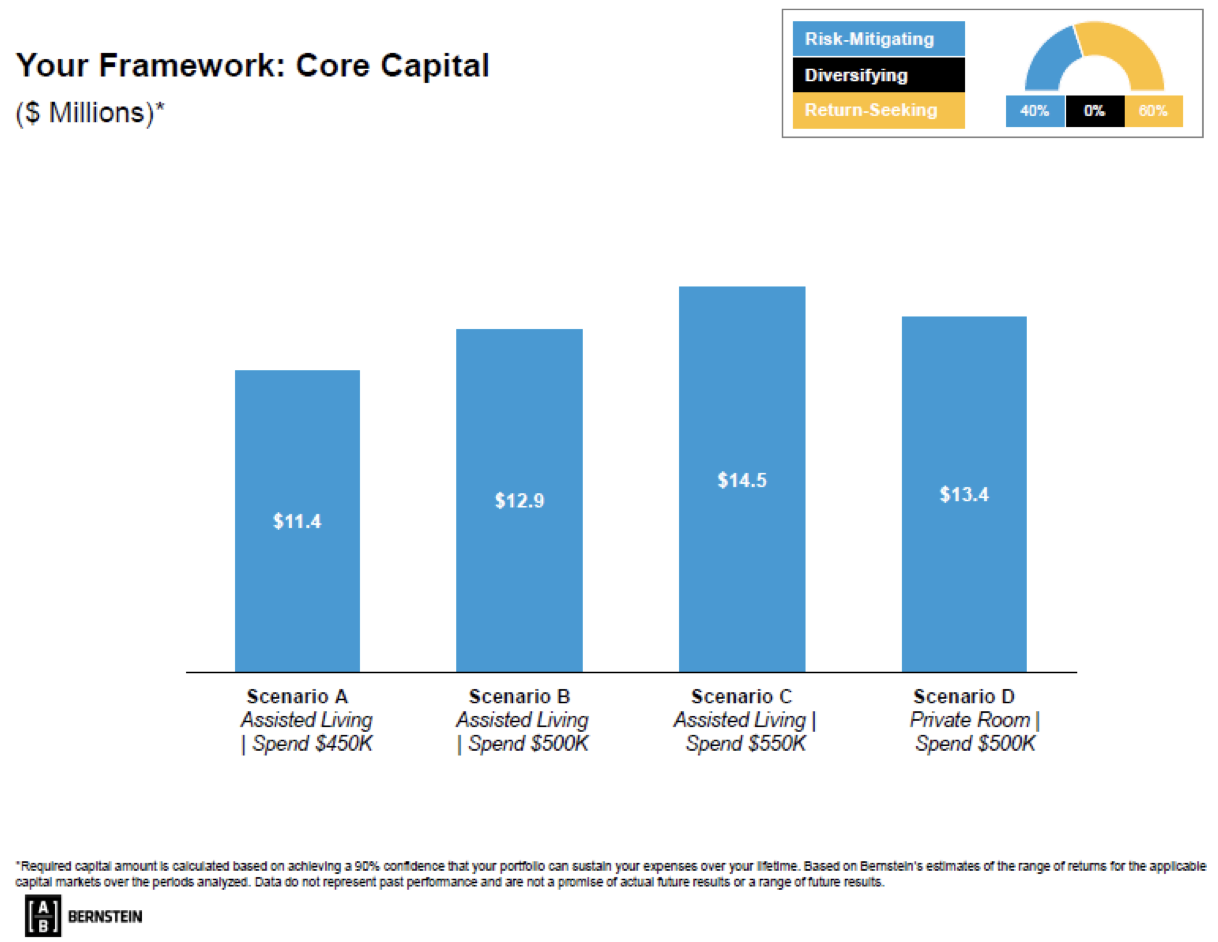

Regarding her transfer tax planning strategies, Layla’s counsel suggests she work with her financial advisor to calculate how much liquidity Layla needs to retain to support her lifestyle for the balance of her lifetime with a high degree of confidence (i.e., her “core capital”). With an asset allocation of 60% equities and 40% fixed income, and an expectation that Layla will move from her current home to an apartment by age 70 and then ultimately to assisted living by age 85, her financial advisor estimates that Layla’s core capital needs range from $11.4 to $14.5 million, depending on her spending levels. Thus, if Layla maintains her current spending of $450,000 a year, she has around $3.6 million of “surplus capital” that she could utilize to make additional gifts to other individuals or charities. However, if she requires additional support, including at-home care, the services of a professional fiduciary, or a private room—such additional costs could significantly reduce this surplus. Further, Layla is still unsure who to benefit with the transfer of her surplus capital.

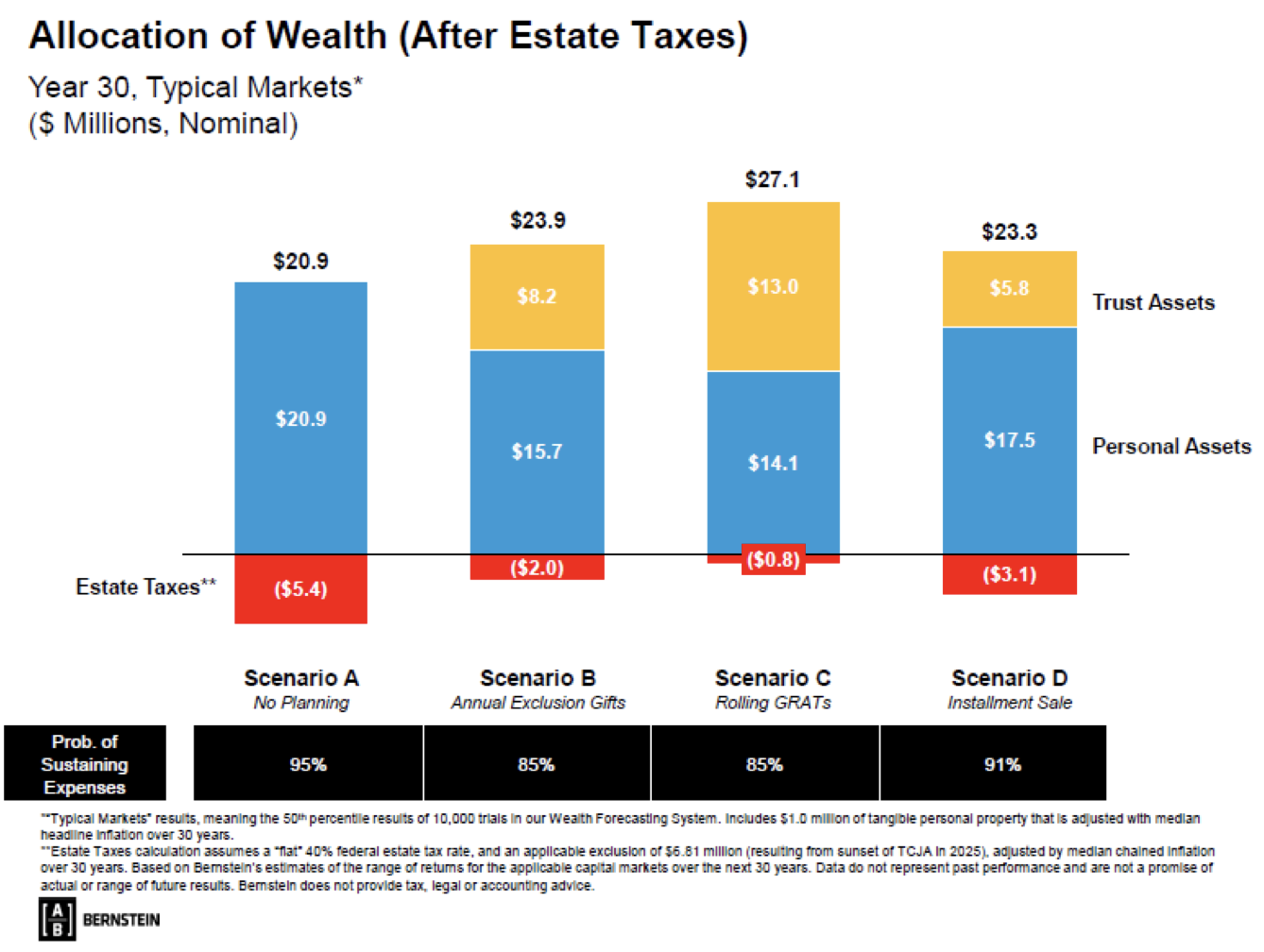

In response to her lingering uncertainty, Layla’s advisors suggest using a few different strategies to allow her to limit her federal estate tax exposure without hindering her current and future lifestyle needs. Namely, they recommend that she consider funding a nongrantor irrevocable trust that can benefit her nieces and nephews, friends, and neighbors (a “friends and family trust” or “FFT”) by: (i) making annual exclusion gifts for the benefit of five (5) beneficiaries each year, (ii) contributing $3 million to a series of zeroed-out, 2-year rolling GRATs for 20 years,[lxxxi] and/or (iii) contributing $300,000 to the FFT and selling $2.7 million of marketable securities to the FFT in exchange for a 20-year, interest-only, balloon promissory note that accrues interest at the long-term applicable federal rate of 4.37%. Layla’s advisors demonstrate that in median markets, the annual exclusion gifts alone will eliminate $3.4 million of federal estate tax. The rolling GRAT strategy performs even better with a residual federal estate tax liability of only $800,000. Even the sale of securities to the FFT, which underperforms the other two scenarios, manages to reduce her estate tax liability by $2.3 million. Layla decides to begin with the rolling GRAT strategy and switch to simple annual exclusion gifts if markets turn sour or her spending needs change.

When Layla asks about her ability to alter the FFT’s beneficiaries as her living situation or relationships evolve, her counsel informs her that an independent trustee may decant the trust’s assets to a new trust for the benefit of some, but not all, of the original trust’s beneficiaries. This allays Layla’s concern about falling out with any of the trust’s beneficiaries or how the trustee would separate certain beneficiaries from each other to address any conflicts among them. However, Layla still wonders about the ability to add beneficiaries in the future. In response, her counsel walks her through the options of a limited power of appointment, utilizing a trust protector, or even establishing a noncharitable purpose trust. While Layla considers granting her siblings a limited power of appointment over the trust exercisable either during each sibling’s lifetime or at their death, she worries that her siblings’ ages might cut this strategy’s viability short as she is the youngest of her three siblings. For a longer-term solution, Layla wants to explore the idea of a noncharitable purpose trust designed to support the individuals within her social network. While Layla’s home state does not have a noncharitable purpose trust statute that fits her needs, Layla can create the trust under Tennessee’s statute by naming her sister -a Tennessee resident- as its trustee.

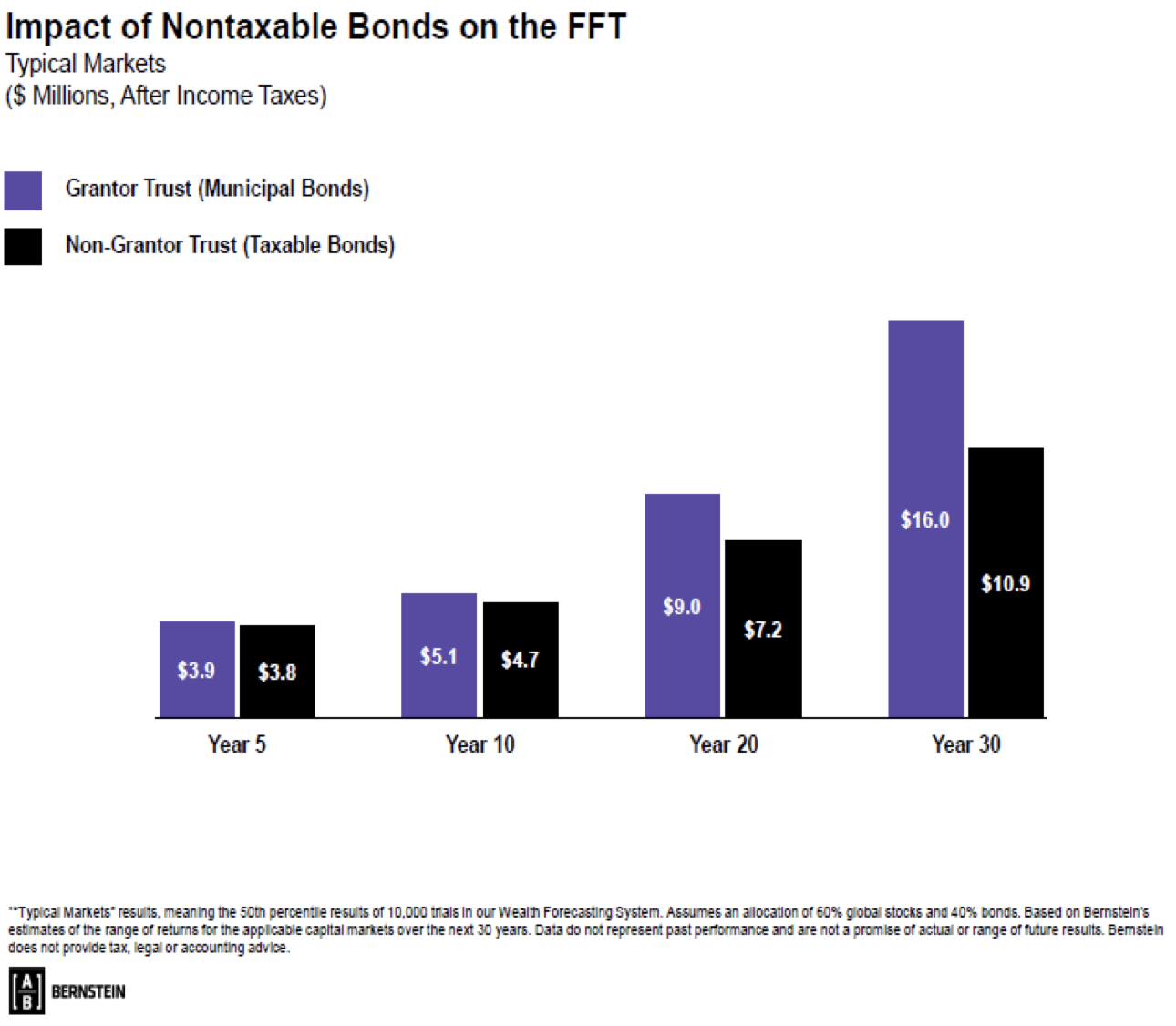

Yet this means that the FFT will likely qualify as a grantor trust as to Layla, raising concerns about her liquidity levels. More specifically, Layla will need to support not only the funding of the trust but also pay the trust’s income tax liability without access to the trust funds. When Layla asks what she can do to limit her income tax burden, her advisors suggest that she consider using nontaxable bonds for a portion of the trust’s portfolio. However, Layla worries that this might negatively impact the trust’s investment performance, and she asks her advisors to determine the financial impact if she moves forward with a grantor trust contingent on the use of nontaxable fixed income.

When Layla’s advisors model the projected growth of a portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% nontaxable bonds held inside a grantor trust, this portfolio grows faster than a portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% taxable bonds within a trust that pays its own income taxes. That is, the ability of trust assets to grow without any tax drag more than makes up for any difference in the income levels produced by the two bond portfolios. Based on these findings, Layla moves forward with the FFT as a noncharitable purpose trust as she feels comfortable that a mandate under the trust agreement to invest in nontaxable bonds will not hinder the portfolio’s growth -or the trustee’s ability to achieve the trust’s designated purpose.

With respect to the FFT’s administration, Layla’s counsel suggests naming her brother as an “enforcer” tasked with ensuring execution of the trust’s stated purpose and granting the last surviving sibling the ability to name successors to such roles. Additionally, counsel suggests using a directed trust structure to formally divide up the trustee’s fiduciary roles so that her sister can rely on a corporate trustee to manage the administrative tasks that might otherwise prove too burdensome. Layla’s counsel also recommends building a waiver of certain trustee reporting requirements into the FFT to protect Layla’s privacy as well as leaving a letter of intent for her siblings regarding Layla’s goals for the trust, its investments, and its administration.

[End Case Study]

Inheritance Tax

In addition to planning for potential federal gift and estate tax issues, childfree individuals are more likely to fall subject to an inheritance tax if living in a state that imposes one. Currently, in 2024, only six states impose an inheritance tax: Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.[lxxxii] Although these taxes differ in certain ways, they generally apply to the receipt without consideration of: (i) real or tangible personal property held in a tax-imposing state at the decedent’s date of death, and (ii) the intangible personal property of a resident decedent. The transfer of property prior to death may not avoid an inheritance tax liability as most inheritance tax systems feature a “look-back” period that includes property transferred during a set number of years prior to death and property over which a decedent retained certain levels of control or enjoyment.[lxxxiii] Such taxes typically exempt transfers to ancestors, descendants, and siblings, or at least impose a much lower tax burden on such individuals. However, all these taxes apply to transfers to extended family members and unrelated parties, such as chosen family members.[lxxxiv]

To avoid such taxation, counsel working with a childfree client may consider hedging smaller transfers against the client’s mortality risk. For example, staggered transfers over a longer time horizon may move substantial wealth to a chosen family member free from inheritance tax with only one or two final transfers triggering taxation under an applicable look-back period. Additionally, counsel may consider relying on an exception from inheritance tax for transfers for fair and adequate consideration.[lxxxv] Similar to the federal gift tax system, for the inheritance tax system, an exchange of property of equal value, rather than a gift, is excluded from inheritance tax. For this reason, transfers such as sales to IDGTs or zeroed-out GRATs should avoid such inheritance tax. Lastly, most inheritance tax systems exclude insurance proceeds from taxation, provided the life insurance policy does not pay death proceeds to the decedent’s estate.[lxxxvi] Thus, a childfree client may leverage small gifts to pay life insurance premiums for an inheritance tax-free payout at the client’s passing.

Case Study

Let’s return to Layla but assume that she is now a resident of Bethesda, Maryland. Layla now wishes to leave $2 million in trust to her nieces and nephews, free of inheritance tax. How should she accomplish this goal?

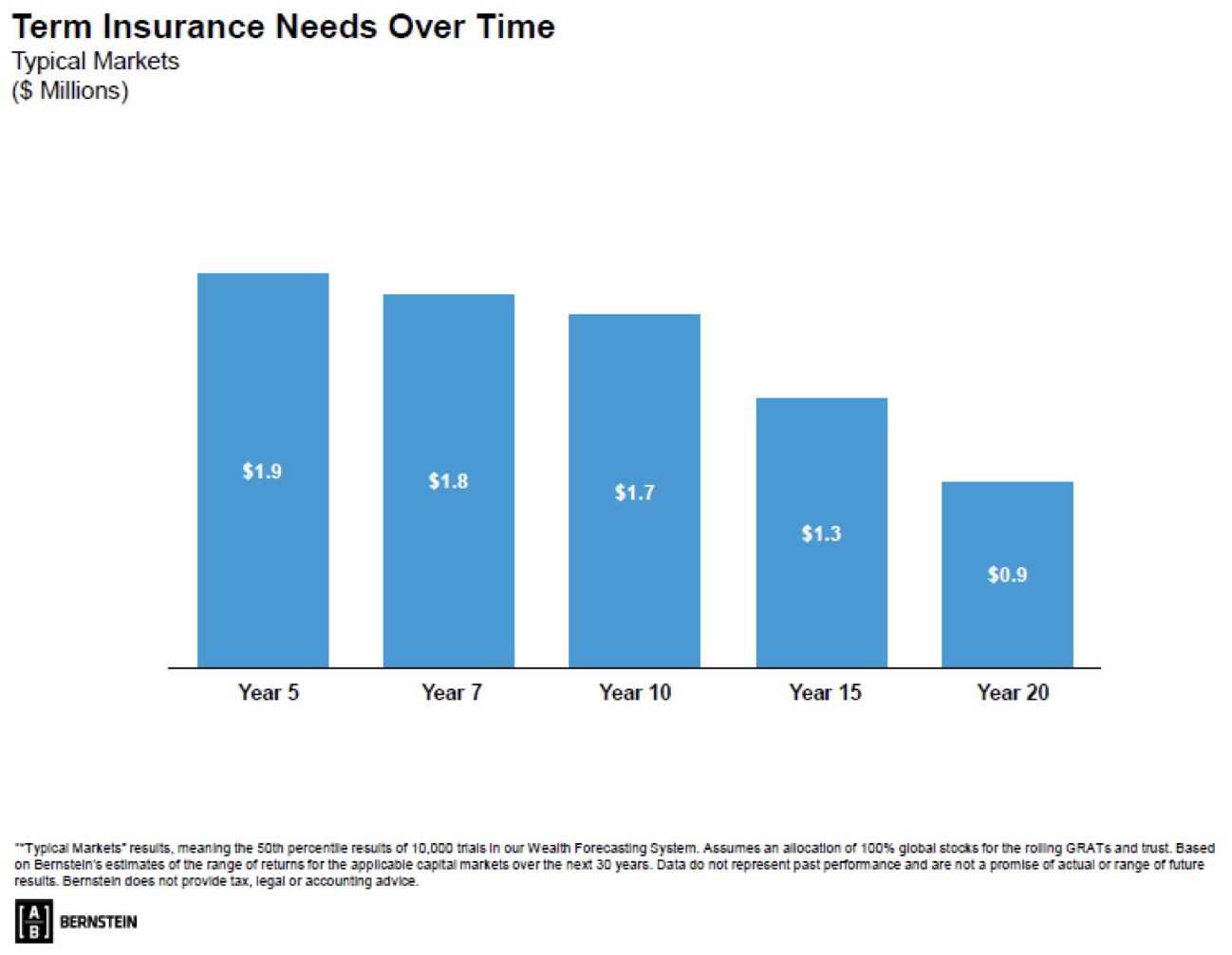

In this case, Layla’s most direct path is to fund the trust with $2 million today with the knowledge that she will likely outlive the 2-year look-back period imposed under Maryland’s inheritance tax.[lxxxvii] But what if she does not want to part with such a sizeable sum at this stage of her life? In that case, her counsel could suggest a staggered gift with a life insurance hedge. Layla could fund a zeroed-out, 2-year rolling GRAT series for 20 years with $500,000. Under median markets, this should deliver $2 million to the remainder trust by year 30. Of course, this means that Layla may leave less than $2 million in trust if she dies before the rolling GRAT term ends. Any bequest that Layla might leave under her will or her revocable trust to bring the ultimate trust value up to $2 million will trigger an inheritance tax liability. To solve for this shortfall in a tax-efficient manner, the trust could purchase staggered life insurance policies to deliver a decreasing death benefit over time (see display). Since life insurance paid to someone other than the decedent’s taxable estate escapes Maryland inheritance tax, this strategy should ensure that Layla’s nieces and nephews receive Layla’s desired after-tax gift.

[End Case Study]

Incorporating Charitable Goals

As noted above, childfree clients may wish to include charitable gifts under their estate plans at their death, even if they do not engage in lifetime charitable giving. In fact, experimental research suggests that this group is more responsive than others to suggested charitable bequests.[lxxxviii] For this reason, counsel should not assume that a lack of past giving practices forestalls the possibility of testamentary charitable transfers. Further, a childfree client may find testamentary, or testamentary-like transfers, especially appealing due to potential liquidity concerns. For example, consider a charitable remainder unitrust that provides the client with a steady stream of payments throughout their lifetime and transfers any property remaining at the client’s death to one or more charities. This planning can assuage any concerns about liquidity needs in connection with end-of-life care while building toward a charitable legacy for the client.

A childfree client may also benefit from an in-depth discussion of legacy and values to uncover an appropriate charitable beneficiary and giving vehicle. As such clients may identify more strongly with a transfer recipient than clients with children and look to charitable giving as a substantial portion of their legacy, counsel may consider casting the potential beneficiary net particularly wide, even to the extent of including nontraditional candidates. For example, an entrepreneurial client may see transfers to other entrepreneurs from their same community or in their same professional field as a desirable form of “charity,” despite the lack of income or estate tax benefits for such transfers to noncharitable recipients. Indeed, planning professionals may see an increase in the overlap of individuals choosing to remain childfree and individuals engaging in nontraditional giving as these trends on the rise in tandem.[lxxxix] After identifying the causes that matter the most to the client and any catalysts that drove past charitable gifts, counsel may wish to include the client’s other advisors in establishing relationships with related organizations and further determining the location, timing, and budget for the client’s charitable plan.

This conversation should also extend to the client’s desired gift restrictions and goals for the gift’s longevity. While beneficiary flexibility may play a key role for the childfree client with respect to noncharitable transfers, flexible provisions such as allowing a trustee to name one or more charities based on a client’s past giving behavior may not best suit clients who are childfree. Rather, the childfree client may benefit from additional efforts to construct a gift agreement that can lay out terms for the gift’s use. Alternatively, the childfree client may prove a good fit for a perpetual charitable vehicle, whether structured as a private foundation or a donor-advised fund.[xc] Notably, however, the client will need to address the need for administrative assistance in operating any ongoing vehicle and engage with professional advisors for this task if those in the client’s personal network are not suited to or interested in this role.

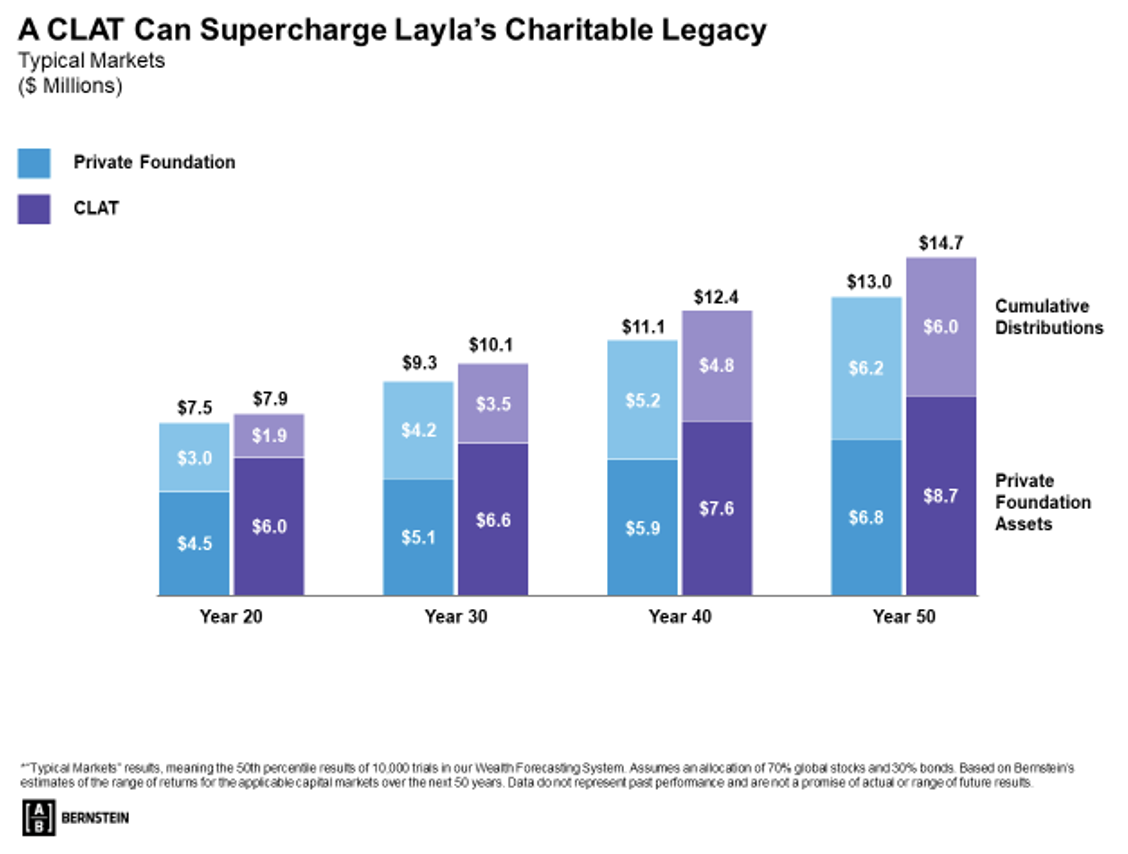

Clients who are looking to establish a long-lasting charitable impact may benefit from grouping resources with others to support established endowments or other long-term efforts of an independent charity. Alternatively, such clients may look to split-interest trusts to deliver smaller gifts over time and satisfy some element of their noncharitable goals. This may prove especially important for those looking to create a private foundation required to distribute 5% of its noncharitable assets each year. For example, the client may choose to create a charitable lead annuity trust (a “CLAT”) at death that distributes a level annuity payment to a private foundation over time. All remaining assets would then be distributed at the end of the trust’s term to a noncharitable beneficiary—which could include chosen family members or even a non-exempt entity such as a 501(c)(4) or social fundraising entity. By spreading the asset transfer over time, the client can limit the reach of the private foundation’s mandatory distribution requirement and extend the duration of the entity’s existence.[xci]

Case Study

Let’s revisit Layla’s planning scenario one last time but turn our focus to her charitable giving goals. Layla’s advisors have proposed a solution that addresses both her residual federal estate tax exposure and her desire to establish a charitable legacy that reflects her firsthand experiences with women’s health issues. Specifically, her advisors recommend that she leave $3.5 million at her death to a charitable vehicle dedicated to advancing research on medical conditions that disproportionately affect women. Given Layla’s interest in having her chosen family exercise full control over the entity and receive compensation for their efforts, Layla’s advisors recommend that she establish a private foundation. Layla views this structure as a central part of her legacy and wants to consider all avenues to amplify its impact over the long term. As such, her advisors suggest funding the foundation through an intermediary CLAT. They run an analysis comparing the remaining funds in the foundation and all prior distributions if Layla funds the foundation either through a direct gift or a CLAT. In doing so, they assume the CLAT makes annual distributions of $276,106 under a Section 7520 rate of 4.8%, and 5% distributions each year for 50 years (as shown below). Layla is surprised to find that, due to the lower exposure to the 5% mandatory distribution rule earlier in the analysis, the CLAT-funded foundation ends up with nearly $2 million more in year 50, despite making overall distributions similar to the direct gift alternative. Layla’s desire to make a lasting impact on the lives of women leads her to move forward with establishing a CLAT upon her passing. This CLAT will provide ongoing support for a private foundation that aligns with her values and bears her name, ensuring that her philanthropic legacy endures for as long as possible.

[End Case Study]

Tailoring Estate Planning for Childfree Clients

While childfree individuals share similarities with parents, estate planning for this client base may require a unique approach that considers their diverse personal networks, spending habits, and charitable giving tendencies. Such reassessment and creative problem-solving may even result in new structures and strategies to meet their needs. Indeed, by questioning certain underlying assumptions regarding the appointment of fiduciaries, the role of flexibility in charitable and noncharitable planning, and the ways in which we define one’s family, planning professionals may uncover better ways to serve all clients in a future that is wide open to parents and nonparents alike.

For illustrative purposes only, and does not constitute an endorsement of any particular wealth transfer strategy. Bernstein does not provide legal or tax advice. Consult with competent professionals in these areas before making any decisions.

The Bernstein Wealth Forecasting SystemSM uses a Monte Carlo model that simulates 10,000 plausible paths of return for each asset class and inflation and produces a probability distribution of outcomes. Moreover, actual future results may not meet Bernstein’s estimates of the range of market returns, as these results are subject to a variety of economic, market, and other variables. Accordingly, the analysis should not be construed as a promise of actual future results, the actual range of future results, or the actual probability that these results will be realized.

BPWM-609096-2024-09-19

Jennifer B. Goode is a National Director of Bernstein Private Wealth Management’s Institute for Trust and Estate Planning in the Washington, D.C. office. In this role, Jennifer works with Bernstein clients and their professional advisors to develop comprehensive wealth management and wealth transfer strategies. Her articles about tax and estate planning have appeared in a number of publications, including the ABA’s Real Property, Trust and Estate Law Journal, Bloomberg’s Tax Management Estates, Gifts, and Trusts Journal, and Practical Law, and she was recently recognized as Bloomberg Tax’s 2023 Estates, Gifts, and Trusts Tax Contributor of the Year. Jennifer frequently presents to professional groups across the U.S. on topics relating to the intersection of estate planning and investing, including a recent appearance at the 58th Annual Heckerling Institute on Estate Planning. Prior to joining Bernstein, Jennifer was a Founding Partner of Birchstone Moore LLC, a Washington, D.C., boutique law firm focused on estate planning and estate and trust administration.

[i] Brady E. Hamilton, et al., Births: Provisional Data for 2023, Vital Stat. Rapid Release, Report No. 35, April 2024, 1, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr035.pdf; CDC, National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Fertility Rate Drops to Another Historic Low, April 25, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2024/20240525.htm.

[ii] Rachel Minkin, et al., The Experiences of U.S. Adults Who Don’t Have Children, Pew Res. Center, July 2024, 1, 5, https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2024/07/PST_2024.7.26_adults-without-children_REPORT.pdf. Notably, only 32% of nonparent participants over age 50 stated that they never wanted children, suggesting that the choice to remain childfree may be rising in popularity. Id.

[iii] Zachary P. Neal & Jennifer Watling Neal, Prevalence, Age of Decision, and Interpersonal Warmth Judgements of Childfree Adults, Sci. Rep. 12, 11907 (2022), 1, 3, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-15728-z.

[iv] Kim Ward, Study: One in Five Adults Don’t Want Children – and They’re Deciding Early in Life, MSU Today, July 25, 2022, https://msutoday.msu.edu/news/2022/One-in-five-adults-dont-want-children.

[v] Jennifer Watling Neal & Zachary P. Neal, Prevalence and Characteristics of Childfree Adults in Michigan (USA), PLoS ONE 16(6): e0252528 (2021), 1, 1-2, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0252528. Additionally, many past studies focused exclusively on women, thereby ensuring results not representative of the entire childfree population. Id.

[vi] The term “chosen family” or “family of choice” has long been used within lesbian, gay, transgender, and queer (“LGBTQ”) communities to describe family groups created by choice rather than biology or legal standing. Nina Jackson Levin, et al., “We Just Take Care of Each Other”: Navigating ‘Chosen Family’ in the Context of Health, Illness, and the Mutual Provision of Care Amongst Queer and Transgender Young Adults, Int’l J. Envtl. Res. & Pub. Health, 2020, 17(19):7346, 1, https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/19/7346.

[vii] Neal & Neal, supra note v, at 13 (after controlling for demographic characteristics, the researchers observed no difference in life satisfaction and limited differences in the five personality characteristics studied, although childfree individuals were more politically liberal than parents). See also Minkin, et. al., supra note ii, at 19 (finding that a majority of nonparent survey participants aged 50 and over say that a person’s ability to have a fulfilling life has nothing to do with having children).

[viii] Marco Albertini & Martin Kohli, What Childless Older People Give: Is the Generational Link Broken?, Ageing and Soc’y 29, 2009, 1261, 1262-63, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231948092_What_Childless_Older_People_Give_Is_the_Generational_Link_Broken; see also Minkin, et. al., supra note ii, at 26 (finding that a quarter of married nonparent survey participants aged 50 and older report that not having children had a positive impact on their marriage, with the childfree participants especially likely to report this impact) and 29 (finding that a majority of nonparent survey participants who had nieces or nephews reported feeling close to at least one niece or nephew).

[ix] Interestingly, a 2009 study found that nonparents were more likely to give and receive financial and social support to and from nonrelatives and relatives of their own or a prior generation, rather than to descendants such as nieces or nephews. Albertini & Kohli, supra note viii, at 1269-70.

[x] Sebastian Schnettler & Thomas Wöhler, No Children in Later Life, but More and Better Friends? Substitution Mechanisms in the Personal and Support Networks of Parents and the Childless in Germany, Ageing & Soc’y 36, 2016, 1339, 1347, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ageing-and-society/article/no-children-in-later-life-but-more-and-better-friends-substitution-mechanisms-in-the-personal-and-support-networks-of-parents-and-the-childless-in-germany/9A897BA0DC89525022A8342D6D478F75.

[xi] Id. at 1356-57 (finding that nonparents had smaller networks in later life due to an absence of children and grandchildren but were able to generate similar levels of support as that received by parents). Notably, when parents are divided into two groups—parents with at least one child living within two hours travel time (“regional parents”) and those with all children living at least two hours away (“remote parents”)—there was no difference in the level of support provided by extended family to nonparents and remote parents. By contrast, the level of support provided by non-family members was higher for nonparents as compared to both groups of parents. This may suggest a special relationship between nonparents and the friends and neighbors in their personal networks. Alternatively, it may suggest that remote parents start developing family-like relationships with nonrelatives later in life as their interaction with their children lessens. Id. at 1352.

[xii] Albertini & Kohli, supra note viii, at 1269.

[xiii] R. Andrew Shippy, et al., Social Networks of Aging Gay Men, J. of Men’s Stud., Vol. 13, No. 1, Fall 2004, 107, 114, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/427896790.

[xiv] Id.

[xv] Id. at 119.

[xvi] Id. at 117.

[xvii] Michael Hurd, Intervivos Giving in the Older Population: Who Receives Financial Gifts from the Childless?, Ageing and Soc’y 29, 2009, 1207, 1214, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ageing-and-society/article/intervivos-giving-by-older-people-in-the-united-states-who-received-financial-gifts-from-the-childless/6D4C4CD30289D09A3B6BBBF98F05A317 (finding that nonparents were between approximately 3 to 5 times more likely to give to friends or relatives -other than their own parents- than those with children across all income and wealth quartiles).

[xviii] Id. at 1223-1224.

[xix] Id. (finding that having children did not impact levels of charitable giving between the two groups and only slightly negatively impacted parents’ levels of giving to their own parents).

[xx] See also Albertini & Kohli, supra note viii, at 1269.

[xxi] Christian Deindl & Martina Brandt, Support Networks of Childless Older People: Informal and Formal Support in Europe, Ageing & Soc’y, 37, 2017, 1543, 1562, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ageing-and-society/article/abs/support-networks-of-childless-older-people-informal-and-formal-support-in-europe/E18395E3136198D4A31769BA86F3FD7F; see also Schnettler & Wöhler, supra note x, at 1343.

[xxii] Minkin, et. al., supra note ii, at 20.

[xxiii] Deindl & Brandt, supra note xxi, at 1547 and 1562.

[xxiv] Sara M. Moorman, Age Integration in the Social Convoys of Young and Late Midlife Adults, Advances in Life Course Res., Volume 56, 2023, 100540, 1, 6, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1040260823000151?via%3Dihub.

[xxv] Minkin, et. al., supra note ii, at 22.

[xxvi] Genworth, Cost of Care Survey, 02/22/24, https://www.genworth.com/aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care.

[xxvii] Christine Fletcher, 5 Things You Should Know About Trustee Fees, Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/christinefletcher/2024/07/29/trustee-fees–top-5-things-you-should-know/.

[xxviii] Hurd, supra note xvii, at 1221. See also Russell N. James, III, The Myth of the Coming Charitable Estate Windfall, Am. Rev. of Pub. Admin., Vol. 39, No. 6, 2009, 661, 670-1, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0275074008326188?download=true&journalCode=arpb.

[xxix] Russell N. James, III, Health, Wealth, and Charitable Estate Planning: A Longitudinal Examination of Testamentary Charitable Giving Plans, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Q., Vol. 38, No. 6, 2009, 1026, 1039, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0899764008323860. Curiously, a separate study that asked parents and nonparents about the probability of including charity under their wills, rather than whether such a provision already existed, did not report the same discrepancy. Query whether this simply reflects the likelihood of parents to consider a charitable bequest prior to completing the estate planning process. Hurd, supra note xvii, at 1221-2.

[xxx] Russell N. James, III, The Ten Most Painful and Pleasant Statistical Realities in Bequest Fundraising, 1, 4, https://www.pgcalc.com/sites/default/files/outline23i0sem.pdf.

[xxxi] Russell N. James, III, American Charitable Bequest Transfers Across the Centuries: Empirical Findings and Implications for Policy and Practice, 12 Est. Plan. & Community Prop. L.J. 235, 285 (2020).

[xxxii] Id. at 283-5.

[xxxiii] Id.

[xxxiv] Id. at 285. Researchers have noted the impacts of parenthood as a social identity when tracking the interpersonal warmth demonstrated by parents toward other parents as compared to that demonstrated by parents toward childfree individuals. More specifically, when asked how warmly they felt toward individuals with and without children, parents reported feeling significantly warmer toward other parents than they did toward childfree individuals. For their part, childfree individuals reported similar levels of warmth toward parents and other childfree individuals. Researchers suggested that parents’ in-group favoritism may stem from social acceptance of parenthood as a significant part of one’s identity, especially as compared to the lack of awareness around and comfort with the childfree lifestyle. Neal & Neal, Prevalence, Age of Decision, and Interpersonal Warmth Judgements of Childfree Adults, supra note iii, at 4.

[xxxv] Frank Adloff, What Encourages Charitable Giving and Philanthropy?, Ageing and Soc’y, 29, 2009, 1185, 1194, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ageing-and-society/article/abs/what-encourages-charitable-giving-and-philanthropy/9755393D5A78A702340D808C34C3D2B6.

[xxxvi] Id.

[xxxvii] The Foundation Center, Highlights of Perpetuity or Limited Lifespan: How Do Family Foundations Decide? Intentions, Practices, and Attitudes, April 2009, 1, https://candid.issuelab.org/resources/13587/13587.pdf.

[xxxviii] Id.

[xxxix] See Britney M. Wardecker & Jes L. Matsick, Families of Choice and Community Connectedness: A Brief Guide to the Social Strengths of LGBTQ Older Adults, J. of Gerontological Nursing, Vol. 46, No. 2, 2020, 5-8, Table 1, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8363185/ (providing sample questions to healthcare providers to inquire about LGBTQ older adults’ families of choice and/or social networks).

[xl] See Deindl & Brandt, supra note xxi, at 1562.

[xli] See Uniform Power of Attorney Act (2006), § 201(a) (“An agent under a power of attorney may do the following on behalf of the principal or with the principal’s property only if the power of attorney expressly grants the agent the authority and exercise of the authority is not otherwise prohibited by another agreement or instrument to which the property is subject… (5) delegate authority granted under the power of attorney”.) To date, 32 states have adopted this Act or a substantially similar version of it.

[xlii] See Uniform Power of Attorney Act (2006), § 114(g) (“An agent that exercises authority to delegate to another person the authority granted by the principal or that engages another person on behalf of the principal is not liable for an act, error of judgment, or default of that person if the agent exercises care, competence, and diligence in selecting and monitoring the person.”).

[xliii] See Uniform Power of Attorney Act (2006), § 111(b) (“A principal may grant authority to designate one or more successor agents to an agent or other person designated by name, office, or function.”).

[xliv] Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”) § 2503(b).

[xlv] To solve for concerns about a future lack of liquidity or resources, counsel may consider including the client among the pool of potential appointees. However, this strategy may result in estate tax inclusion under the common law relation-back doctrine if the trust is not established in a state that grants creditor protection to self-settled trusts. See In re Wylie’s Estate, 342 So. 2d 996, at pp. 998-999 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1977); Restatement (Third) of Prop. § 17.4 (Am. L. Inst. 2011). Additionally, this strategy may result in estate inclusion under IRC § 2036(a)(1) if the facts and circumstances of the trust’s funding and administration demonstrate an understanding that the client and the powerholder intended to facilitate the client’s retained access to the trust’s assets. See Jennifer B. Goode, Sizing a Transfer Tax Strategy for Success, Tr. & Est., September 2023, 28-38.

[xlvi] If this power is granted to the client, it will trigger incomplete gift status under IRC § 2511 and inclusion of the trust assets in the client’s taxable estate under IRC §§ 2036 and 2038. Treas. Reg. § 25.2511-2(c), Treas. Reg. § 20.2036-1(b)(3), and Treas. Reg. § 20.2038-1(a)(3). Further, if this power were held by a trust beneficiary without limiting its exercise in favor of the beneficiary to distributions for health, education, maintenance, and support, it would trigger inclusion of the trust assets in the powerholder’s taxable estate under IRC § 2041. Treas. Reg. § 20.2041-1(c)(2).

[xlvii] Treas. Reg. § 25.2514-1(b)(2) (stating that a mandatory income beneficiary who exercises the right to appoint the trust corpus during lifetime to the beneficiary’s children has exercised a taxable gift) and Treas. Reg. § 25.2514-3(e), Example 2 (stating that the lapse of a power to have income distributed to the powerholder under an ascertainable standard is not a taxable gift). It may also be possible to avoid a taxable gift by granting the powerholder a fully discretionary interest—rather than a mandatory one—but the IRS has taken a contrary position in the past. I.R.S. Priv. Letter Rul. 8535020 (May 30, 1985).